| Return to main page |

After leaving you at Auschwitz on Saturday evening, Professor Dylag and I drove to visit our relatives in the countryside. On Sunday morning we went along with them to mass in the village church. In fact my relatives do not attend mass every Sunday, and nor do the Professor and I here in Cracow. But it is somehow compulsory whenever we visit the village. I think people might comment if we did not attend, and this could reflect badly on my relatives. Anyway, yesterday people did not rush away home after mass, as they usually do. Instead, all of those who had gone by car, the majority, waited patiently in the modern car park for the priest to come along and sprinkle holy water over their vehicle. In Catholic Poland the sprinkling of holy water is a basic form of blessing. Yesterday was the feast day of St. Christopher, the patron saint of travellers. To sprinkle water onto a modern means of transportation is a very simple extension of a very traditional form of ritual and we were quite happy to have our own car blessed in this way. But what is really involved in such a ritual? Do the participants really believe that it has some efficacy? Ö.

|

|

Figure 32: St. Christopher sticker and prayer card

But for your broader assignment this week you should concentrate not on 'political Catholicism' in this overt sense, but on all the less visible ways in which Roman Catholicism permeates the culture of this country. Try to talk to Polish friends about this, ask schoolchildren about the sources of their religious knowledge, and ask ex-communists if they ever came under pressure to declare themselves atheists, and what sort of tensions this created.

|

|

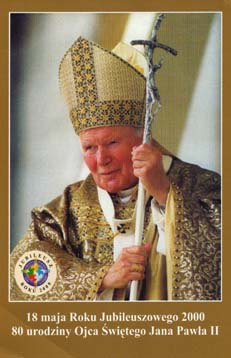

Figure 33: Papal postcard and souvenir stickers

Back in Maria's kitchen, it was not difficult to direct the conversation towards religion. Maria described herself as 'an average sort of Catholic.' This meant that she had made her first communion and had been confirmed, like all of her classmates in Przemysl. She attended mass every Sunday and on holy days of obligation. She did not normally say prayers at other times, though she had gone through a very devout phase a few years earlier, as an adolescent. Her grandmother had died suddenly, and the whole family had found comfort in being able to pay for masses for her soul. Tom said that, for him, that was a custom that belonged in the Middle Ages. 'I have nothing against religion per se, and if some belief in an afterlife leads people to behave a bit more decently in their present, worldly life, then that's great. But how can an institution solicit money to save souls after a person has died? That sounds to me like a recipe for exploiting lots of poor and vulnerable people.'

'I don't think it does any harm,' said Maria. 'People spend their money on plenty of worse things.'

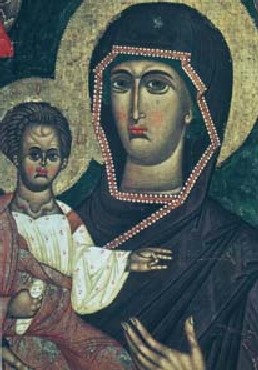

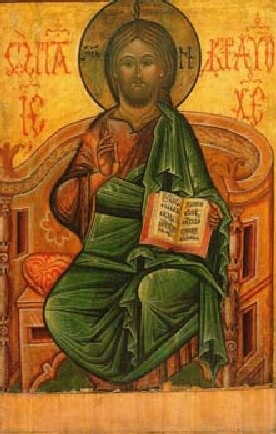

Wlodek said with obvious distaste that some Roman Catholic priests had become capitalist businessmen in the post-socialist period, e.g. by marketing their own brands of alcoholic drink. Ania asked him how often he went to church. To her astonishment he answered that he tried to look in most days to one particular small church which served the city's Greek Catholic parish. His family belonged to this minority. As a youngster in Przemysl he had grown up with the hymns and rituals of this rite. 'It's all the same religion really,' he said, 'only the rite is different.' Now, living away from home for the first time, it was somehow important to him to kneel for a few minutes each day in front of an icon of the Holy Virgin. He joked:

'I try to get Maria to come along, at least on Sundays, but she thinks

the Greek Catholic services drag on a bit too long.'

'You know very well it's not that,' retorted Maria. 'I think the

Greek Catholic services are very beautiful, much more sensuous than ours.

But everything is in Ukrainian, and I really can't follow very much of

it.'

Ania was confused. She had assumed that all Poles were Roman Catholics, but apparently Wlodek was a Greek Catholic, and the language used in their church was not Polish but Ukrainian. Before she could ask a question about this she found herself on the receiving end of a question from Maria:

'And how often do you go to church? We all know that Tom is a lost cause, but I guess the religious element is still important in keeping the community together in London.'

Ania recalled the tedious Sunday school classes she had endured for so many years and admitted that 'organised religion' had no appeal to her whatsoever. She thought it better to keep quiet about the New Age group that she had been introduced to by a boy-friend during her first year at university. She wasn't sure she could explain what that was all about in Polish, and anyway, she was sure that the other three would disapprove.

|

|

Figure 34: Devotional images of Greek Catholics (i) and (ii) and of Roman Catholics (iii)

| Return to main page |