Ex-president Salinas tries to avoid the press in New York after leaving the country under a cloud in 1995.

Having effectively removed state support for peasant agriculture, in 1991, the Salinas government announced that it proposed to amend Article 27 of the Mexican Constitution in a way which would open the way to the eventual privatization of ejido land.

But the land rights certification programme designed to pave the way for privatization, PROCEDE, made scant progress under Salinas in the Ciénega de Chapala. The ejidatarios of this region had good reason to feel nervous about any juridical intervention on matters pertaining to land rights, since the present structure of land tenure was based on what were, before the legislative changes, pervasive illegalities associated with the development of a market in ejidal land titles. Not only had land been concentrated in the hands of "rich ejidatarios" who emerged in the neolatifundist period and persons with little real claim to be considered "peasants"at all, but it had often been acquired by persons not resident in the communities associated with the ejidos. A considerable amount of land is also held by emigrados permanently resident in the United States. At first sight, this would seem to make Salinas’s reform of land tenure legislation attractive to these ejidatarios, since the new laws effectively legalize most of the past illegalities. What complicated the issue was the need to maintain sociability within rural communities in which relations are already very strained.

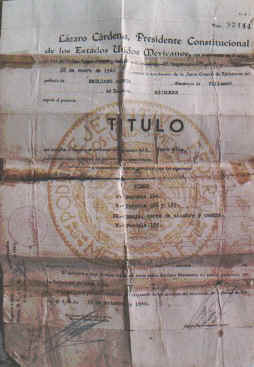

A comparatively rare document. The Guaracha ejidatarios received proper land titles when the ejido was parcellized in 1940, although many of the current holders of the land use titles originally assigned to other persons which they bought illegally, and many do not even hold certificates validating the transfer.

A comparatively rare document. The Guaracha ejidatarios received proper land titles when the ejido was parcellized in 1940, although many of the current holders of the land use titles originally assigned to other persons which they bought illegally, and many do not even hold certificates validating the transfer.

Poorer peasants were convinced that the reform of land law was simply a device to ensure their eviction from the ejidos, and their experience of matters pertaining to land rights in the past gave them little confidence in the transparency and justice of any bureaucratic procedure administered by external officials supported by ejido authorities. Slightly better-off ejidatarios were worried that the land certification process was simply a ruse to make ejidatarios pay additional taxes. The economic position of what was once an ejidal elite had been severely undermined in recent years, making land accumulation of much less direct interest to them than in the past (though some might be willing to act as agents for outsiders). Some were also clearly afraid that state intervention might yet lead to their being deprived of some of their less legitimately acquired or still contested holdings.

In 1990, a longstanding dispute over land between a son and brother of the most important former community cacique, the ex-administrator of Samuel Yepes,took a new and violent turn with the assassination of the older protagonist by his great-nephew, who was able to escape justice and flee to the United States unimpeded because of his family’s good relations with the priísta municipal authorities. It was notable that the SRA (Ministry of Agrarian Reform) official in charge of the decennial depuración del censo (purging of the roll) assembly which took place later in the year wisely accepted the comisariado’s advice to keep the issue "low key". The intellectual author of the crime, himself a former comisariado, prudently failed to attend, secure in the knowledge that his kinsmen and clients would defend his interests and that the rest of the community would not press the issue beyond a token eruption of shouting.

The change to the law added to the support received by the PRD from ejidatarios of the Ciénega, and they also showed interest in the El Barzón anti-debt movement that developed among private farmers in Jalisco.

The change to the law added to the support received by the PRD from ejidatarios of the Ciénega, and they also showed interest in the El Barzón anti-debt movement that developed among private farmers in Jalisco.

Faced with these kinds of problems, it is not surprising that the PROCEDE officials also pursued a strategy of "leaving the difficult communities for later". The Guaracha ejido did, finally, cautiously enter into discussions with PROCEDE officials more than two years after Salinas left office, in 1997, but continued to show little enthusiasm for full land privatization.